WoRMS taxon details

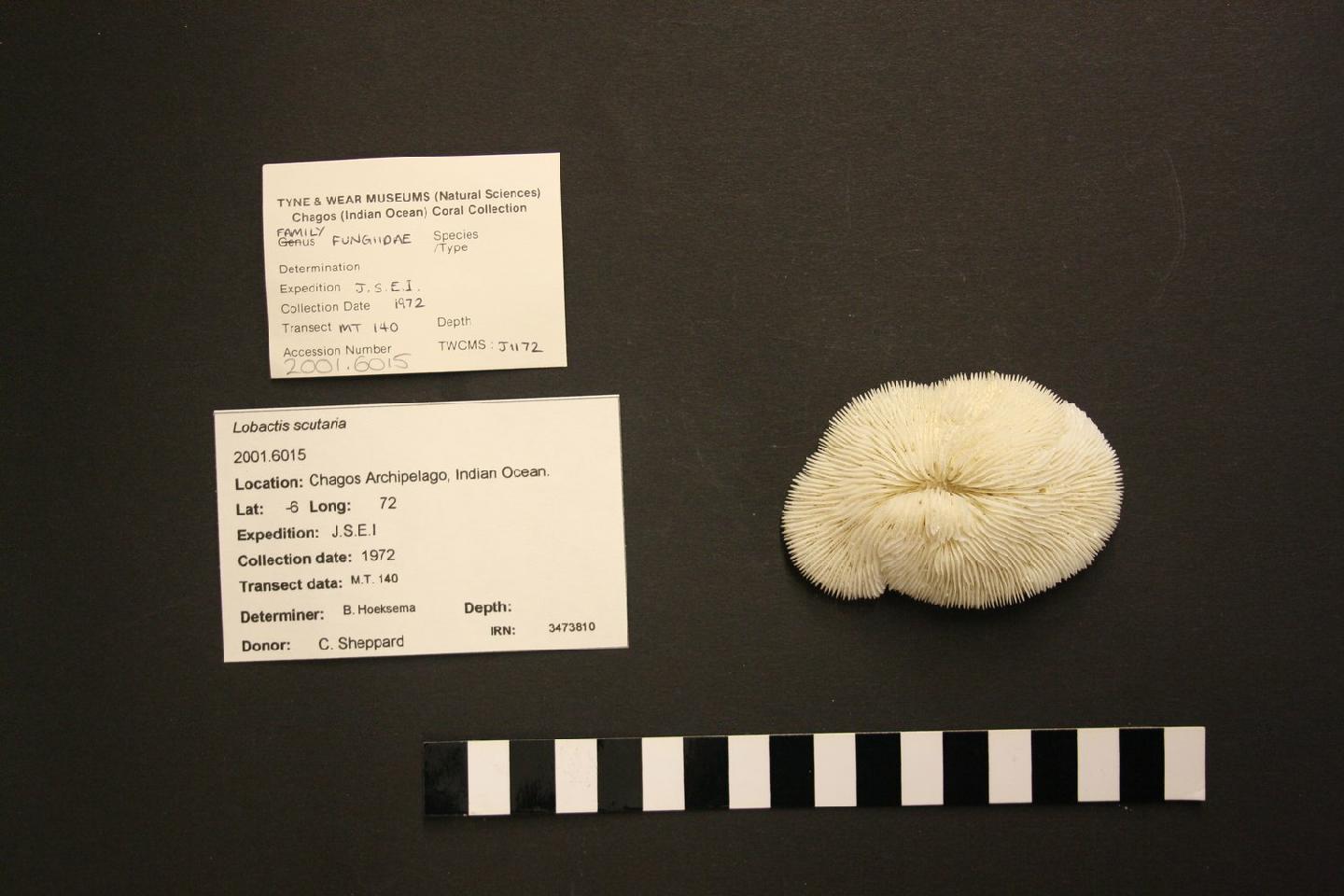

Fungiidae Dana, 1846

196100 (urn:lsid:marinespecies.org:taxname:196100)

accepted

Family

Fungia Lamarck, 1801 (type by original designation)

Funginellidae Alloiteau, 1952 † · unaccepted > junior subjective synonym

- Genus Cantharellus Hoeksema & Best, 1984

- Genus Ctenactis Verrill, 1864

- Genus Cycloseris Milne Edwards & Haime, 1849

- Genus Danafungia Wells, 1966

- Genus Fungia Lamarck, 1801

- Genus Halomitra Dana, 1846

- Genus Heliofungia Wells, 1966

- Genus Herpolitha Eschscholtz, 1825

- Genus Lithophyllon Rehberg, 1892

- Genus Lobactis Verrill, 1864

- Genus Pleuractis Verrill, 1864

- Genus Podabacia Milne Edwards & Haime, 1849

- Genus Polyphyllia Blainville, 1830

- Genus Sandalolitha Quelch, 1884

- Genus Sinuorota Oku, Naruse & Fukami, 2017

- Genus Zoopilus Dana, 1846

- Genus Cryptabacia Milne Edwards & Haime, 1849 accepted as Polyphyllia Blainville, 1830 (unaccepted > junior subjective synonym)

- Genus Diaseris Milne Edwards & Haime, 1849 accepted as Cycloseris Milne Edwards & Haime, 1849 (unaccepted > junior subjective synonym)

- Genus Döderleinia Gardiner, 1909 accepted as Sandalolitha Quelch, 1884 (unaccepted > junior subjective synonym, incorrect original spelling)

- Genus Doederleinia Gardiner, 1909 accepted as Sandalolitha Quelch, 1884 (unaccepted > junior subjective synonym)

- Genus Haliglossa Ehrenberg, 1834 accepted as Herpolitha Eschscholtz, 1825 (unaccepted > junior subjective synonym)

- Genus Hemicyathus Seguenza, 1862 accepted as Cycloseris Milne Edwards & Haime, 1849 (unaccepted > junior subjective synonym)

- Genus Herpetoglossa Wells, 1966 accepted as Ctenactis Verrill, 1864 (unaccepted > junior subjective synonym)

- Genus Herpetolitha Leuckart, 1841 accepted as Herpolitha Eschscholtz, 1825 (unaccepted > junior subjective synonym)

- Genus Herpetolithas Leuckart, 1841 accepted as Herpolitha Eschscholtz, 1825 (unaccepted > junior subjective synonym)

- Genus Herpetolithus Leuckart, 1841 accepted as Herpolitha Eschscholtz, 1825 (unaccepted > junior subjective synonym)

- Genus Lithactina Lesson, 1831 accepted as Polyphyllia Blainville, 1830 (unaccepted > junior subjective synonym, misspelling)

- Genus Lithactinia Lesson, 1831 accepted as Polyphyllia Blainville, 1830 (unaccepted > junior subjective synonym)

- Genus Parahalomitra Wells, 1937 accepted as Sandalolitha Quelch, 1884 (unaccepted > junior subjective synonym)

- Genus Podobacia Milne Edwards & Haime, 1849 accepted as Podabacia Milne Edwards & Haime, 1849 (unaccepted > misspelling - incorrect subsequent spelling)

- Genus Polyphillia Blainville, 1830 accepted as Polyphyllia Blainville, 1830 (unaccepted > misspelling - incorrect subsequent spelling)

- Genus Verrillofungia Wells, 1966 accepted as Lithophyllon Rehberg, 1892 (unaccepted > junior subjective synonym)

- Genus Diafungia Duncan, 1884 (uncertain > taxon inquirendum)

marine, fresh, terrestrial

Dana, J.D. (1846-1849). Zoophytes. United States Exploring Expedition during the years 1838-1842. <em>Lea and Blanchard, Philadelphia.</em> 7: 1-740, 61 pls. (1846: 1-120, 709-720; 1848: 121-708, 721-740; 1849: atlas pls. 1-61)., available online at https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/18989497, http://www.sil.si.edu/digitalcollections/usexex/navigation/ScientificText/USExEx19_08select.cfm [details]

Description Most reef fungiids are free-living . The polyps are among the largest of all corals. These solitary forms have a long...

Description Most reef fungiids are free-living . The polyps are among the largest of all corals. These solitary forms have a long fossil history extending back to the early origins of the Scleractinia. It is therefore likely that the colonial genera have evolved from the solitary ones, rather than the reverse. This theory is supported by the fact that the structure of the septa of each colonial genus has an equivalent in one of the subgenera of Fungia.

As a general rule, corals with one mouth are called solitary and those with many mouths are called colonial, but clearly this distinction is not always well defined, nor is it basic to the structural organisation of several species. Little is known about many very important aspects of the biology of free-living fungiids, especially their population dynamics, food sources and growth rates. One distinct aspect of the daily existence of all but the heaviest fungiids is that they are at least partially mobile. The genera are solitary or colonial, free-living or attached, mostly hermatypic and extant. Colonial genera are derived from solitary genera and each has septo-costal structures corresponding to those of a solitary genus. These septo-costae radiate from the mouth on the upper surface (as septa) and from the centre of the undersurface (as costae). No similar families. (Veron, 1986 <57>). [details]

As a general rule, corals with one mouth are called solitary and those with many mouths are called colonial, but clearly this distinction is not always well defined, nor is it basic to the structural organisation of several species. Little is known about many very important aspects of the biology of free-living fungiids, especially their population dynamics, food sources and growth rates. One distinct aspect of the daily existence of all but the heaviest fungiids is that they are at least partially mobile. The genera are solitary or colonial, free-living or attached, mostly hermatypic and extant. Colonial genera are derived from solitary genera and each has septo-costal structures corresponding to those of a solitary genus. These septo-costae radiate from the mouth on the upper surface (as septa) and from the centre of the undersurface (as costae). No similar families. (Veron, 1986 <57>). [details]

Hoeksema, B. W.; Cairns, S. (2025). World List of Scleractinia. Fungiidae Dana, 1846. Accessed through: World Register of Marine Species at: https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=196100 on 2025-04-05

Date

action

by

![]() The webpage text is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 License

The webpage text is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 License

Nomenclature

original description

Dana, J.D. (1846-1849). Zoophytes. United States Exploring Expedition during the years 1838-1842. <em>Lea and Blanchard, Philadelphia.</em> 7: 1-740, 61 pls. (1846: 1-120, 709-720; 1848: 121-708, 721-740; 1849: atlas pls. 1-61)., available online at https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/18989497, http://www.sil.si.edu/digitalcollections/usexex/navigation/ScientificText/USExEx19_08select.cfm [details]

original description (of Funginellidae Alloiteau, 1952 †) Alloiteau J. (1952). Embranchement des Coelentérés. Madreporaires Post-Paleozoiques. <em>In: Piveteau J, ed. Traité de Paléontologie, Paris: Masson.</em> 539–684, pls. 1-10. [details]

basis of record Hoeksema BW. (1989). Taxonomy, phylogeny and biogeography of mushroom corals (Scleractinia: Fungiidae. <em>Zoologische Verhandelingen, Leiden.</em> 254: 1-295., available online at http://www.repository.naturalis.nl/document/149013 [details]

original description (of Funginellidae Alloiteau, 1952 †) Alloiteau J. (1952). Embranchement des Coelentérés. Madreporaires Post-Paleozoiques. <em>In: Piveteau J, ed. Traité de Paléontologie, Paris: Masson.</em> 539–684, pls. 1-10. [details]

basis of record Hoeksema BW. (1989). Taxonomy, phylogeny and biogeography of mushroom corals (Scleractinia: Fungiidae. <em>Zoologische Verhandelingen, Leiden.</em> 254: 1-295., available online at http://www.repository.naturalis.nl/document/149013 [details]

Other

additional source

Gittenberger A, Reijnen BT, Hoeksema BW. (2011). A molecularly based phylogeny reconstruction of mushroom corals (Scleractinia: Fungiidae) with taxonomic consequences and evolutionary implications for life history traits. <em>Contributions to Zoology.</em> 80: 107-132., available online at https://doi.org/10.1163/18759866-08002002 [details]

additional source Wells JW. (1966). Evolutionary development in the scleractinian family Fungiidae. In: Rees WJ (ed.) The Cnidaria and their evolution. <em>Symposium of the Zoological Society of London Academic Press, London.</em> 16: 223–246, pl. 1. [details]

additional source Veron JEN. (2000). Corals of the World. Vol. 1–3. <em>Australian Institute of Marine Science and CRR, Queensland, Australia.</em> [details]

additional source Wells JW. (1966). Evolutionary development in the scleractinian family Fungiidae. In: Rees WJ (ed.) The Cnidaria and their evolution. <em>Symposium of the Zoological Society of London Academic Press, London.</em> 16: 223–246, pl. 1. [details]

additional source Veron JEN. (2000). Corals of the World. Vol. 1–3. <em>Australian Institute of Marine Science and CRR, Queensland, Australia.</em> [details]

Present

Present  Inaccurate

Inaccurate  Introduced: alien

Introduced: alien  Containing type locality

Containing type locality

From editor or global species database

Diagnosis Corallum monostomatous (solitary) or polystomatous by development of secondary stomata. Corallum zooxantellate, free or attached (on a stalk or encrusting), in some species reproducing by transverse division (autotomy). Corallum wall solid or perforate. Low order septa imperforate, high order septa perforate. Septa laminar and connected laterally by bar-like elements called "compound synapticulae" or "fulturae". Margins of septo-costae variable in shape by simple or complex ornamentation, usually species-specific. Range: Indo-Pacific, shallow water. [details]Unreviewed

Description Most reef fungiids are free-living . The polyps are among the largest of all corals. These solitary forms have a long fossil history extending back to the early origins of the Scleractinia. It is therefore likely that the colonial genera have evolved from the solitary ones, rather than the reverse. This theory is supported by the fact that the structure of the septa of each colonial genus has an equivalent in one of the subgenera of Fungia.As a general rule, corals with one mouth are called solitary and those with many mouths are called colonial, but clearly this distinction is not always well defined, nor is it basic to the structural organisation of several species. Little is known about many very important aspects of the biology of free-living fungiids, especially their population dynamics, food sources and growth rates. One distinct aspect of the daily existence of all but the heaviest fungiids is that they are at least partially mobile. The genera are solitary or colonial, free-living or attached, mostly hermatypic and extant. Colonial genera are derived from solitary genera and each has septo-costal structures corresponding to those of a solitary genus. These septo-costae radiate from the mouth on the upper surface (as septa) and from the centre of the undersurface (as costae). No similar families. (Veron, 1986 <57>). [details]

| Language | Name | |

|---|---|---|

| Japanese | クサビライシ科 | [details] |